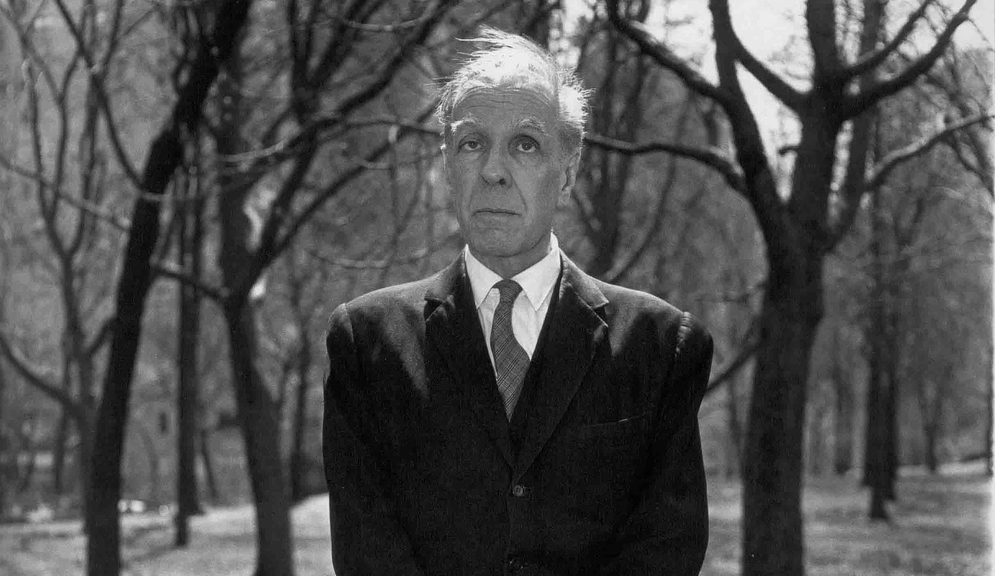

I encountered the work of Jorge Luis Borges while travelling around the Guatemalan highlands last year. I was in Panajachel, a dirty little tourist town which lies in the shadow of a great volcano.

Wandering the streets in the sweltering heat I stumbled across a small, English-language book store. Hungrily scanning its shelves, I picked out a copy of Borges’ Labyrinths alongside Jack London’s Call of the Wild and Salman Rushdie’s East/West.

Borges’ name seemed familiar; I could half-remember his world of Tlön in John Gray’s The Silence of Animals. After reading the book jacket’s reference to “groundbreaking writing that is multi-layered, self-referential, elusive, and allusive”, I gambled on a purchase.

The gamble proved to be an excellent one, for I have been mystified by the beauty and intelligence of Borges’ writing.

Describing his style is an intimidating challenge. Borges is credited as a pioneer of “magical realism” (which you may have also seen Murakami’s name attached to), a style which attempts to challenge assumptions about the nature of reality through literary technique.

Most of us take reality to be banal and solid; an immovable foundation. Borges cautioned against this. Through his fiction he hoped to wake readers from the dream of their everyday reality, and rekindle in them a “sacred astonishment” at the mysterious, paradoxical nature of existence.

If this aim seems quasi-religious, that’s because it is. Through mysticism, science and philosophy, humankind has attempted to understand the nature of reality and our relationship to it. Asking questions like “What is Truth?”, “What is Reality?”, and “How should we live?” are amongst the highest tasks of consciousness.

Borges wished to awaken more people to this calling.

In his fictions, Borges often infuses obscure history and philosophy to create lush alternate universes. While each unfolds, the dynamics of each universe slowly becomes clear. Through the process of this illumination Borges passes some reflection on to the reader.

This is his brilliance: the ability to convey the deepest revelations of philosophy within a dozen pages of a short story.

Let’s take Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius as an example.

In this story, Borges conceives of a universe in which humanity has never embraced Descartes’ philosophy of determinism – that is, the idea that the physical world is an enormous chain of cause-and-effect; durable in time, and able to be perceived (and known) by humans.

In the 1600s, Descartes’ ideas helped emancipate humanity from the tyranny of the Church, which claimed that Truth can only be known through the Revealed Word of God. By elevating each individual to a free, rational agent who is able to determine truth for herself through skeptical inquiry, Descartes empowered humanity. His philosophy is a cornerstone of The Enlightenment, and of Western civilisation today.

In Descartes’ place, Borges dreamt of a civilisation built on Berkeley’s notion of solipsism: the idea that the universe has no existence except in the mind which perceives it. Or, to put it more simply; that there is no reality outside of your mind. In such a perspective “things” do not exist, only “happenings” which are unconnected in space or time. This renders determinism void, and the majority of Western philosophy or science, impossible.

By imagining a possible universe with a very different basis for knowledge and perception, Borges demonstrates that much of what we assume to be “true” or “common sense” is actually the result of inherited systems of ideas.

The tale is also one of empowerment. By handing back humanity this creative power he issues the reader a challenge to take more control of the ideas which govern her life, and to realise that we too can create or destroy the laws of the universe within our minds.

The history of humanity is in many ways the struggle against chaos and meaninglessness. It is our task – and burden – to create meaning for ourselves, and to confront the transitory nature of our existence.

This task is not without danger. Mankind’s longing for order can lead it to embrace terrible ideologies. Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is also a cautionary tale against the surety of man-made systems.

As he writes in the story’s faux-postscript:

Ten years ago any symmetry with a semblance of order – dialectical materialism, anti-Semitism, Nazism – was sufficient to entrance the minds of men. How could one do other than to submit to Tlön, to the minute and vast evidence of an orderly planet?

…The contact and the habit of Tlön have disintegrated this world. Enchanted by its rigor, humanity forgets over and again that it is a rigor of chess masters, not of angels.

When the tale of Tlön was published in 1940, the reference to Nazism was particularly poignant. It is a horrific testament to the power of an artificial order. Its architects were not gods, but men.

Borges returned to the theme of the subjective nature of our reality repeatedly throughout his life. Many years later he wrote in the Avatars of the Tortoise:

The greatest magician (Novalis has memorably written) would be the one who would cast over himself a spell so complete that we would take his own phantasmagorias as autonomous appearances. Would not this be our case?

I conjecture that this is so. We (the undivided divinity operating within us) have dreamt the world. We have dreamt it as firm, mysterious, visible, ubiquitous in space and durable in time; but in its architecture we have allowed tenuous and eternal crevices of unreason which tell us it is false.

Borges’ thoughts are clear: our everyday experience is an illusion of our own creation – and if we look at it closely enough, we will see the gaps for ourselves.

The effect of reading Borges’ Labyrinths is intoxicating; magical. You will walk away never again sure of the reality in which you live.

This piece was originally published at The Big Smoke.